According to the British Fashion Council, there are now enough clothes on the planet to dress the next six generations of humans, even taking into account population expansion. What that means is as we buy that new outfit, we contribute to the clothes mounting that charities can’t deal with. Third-world countries don’t want these clothes; they can’t use them all, and it suppresses their own production. It all becomes a destructive cycle of consumer demand, production, consumption and waste. That means the landfills are filling with discarded clothes, and resources are being consumed to make more soon-to-be landfilled clothes. Planet killing pollution, and let’s not forget the subjugation of the global poor as a labour force.

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the global clothing industry is currently valued at 1.3 trillion dollars. Clothing makes up more than 60% of all textiles used, and over the past 15 years, clothing production has doubled. We love our fast fashion! Which involves rapid turnaround of new styles, a higher number of collections released each year, oh and we want it cheap! Much of the fabric is synthetic; its fibres and artificial dyes stubbornly refuse to decay nicely, clogging and poisoning the earth and waterways!

It hasn’t always been like this; the make-do and mend of past times saw value in fabric. Last Saturday, I had the opportunity to participate in a Sashiko workshop with the artist Jac Brill. They have an exhibition at the beautiful small gallery at 2 London Place Borth.

Sashiko is a traditional form of Japanese embroidery or stitching. It is typically used to decorate, reinforce and reuse cloth and clothing. The Japanese word translates as ‘little stabs’, an excellent process description. We were fortunate to have one of our fellow workshop attendees bring an example of Sashiko from Japan, a hat her mother had made for her; it was quite discreet in its decoration and exhibited a modern Japanese simplicity.

Historically, Sashiko was commonly done using white cotton thread on indigo-dyed blue workwear cloth, giving it a unique white-on-blue appearance. Still, eventually, scraps of more precious fabric began to be incorporated into work. Brill’s workshop explored the technique to create textile art and craft jewellery.

Textile art has always been seen as a women’s craft and, as such, has had a lesser significance in historical art terms, which is now beginning to be redressed. That said, the amount of physical work undertaken is not commensurate with remuneration, especially craft pieces. My small but rather lovely necklace took 5hrs to stitch. Brill talks about memory being imbued within stitch work, and she recalled each scrap I used within my piece to the fabric origins, including memories of stitch and textile work with her family. This feeling of community was evident within the workshop, and it became a meditative space, but a tiring one; this is not easy work.

I also have contributed to the Post-Grad Family Heirloom, which is a large-scale collaborative artwork by current postgraduate students and alums from all UAL colleges.

We have each worked on a 40cmX40cm patchwork of art that reflects our practice focus and identity. These will be stitched together at the end of the 23/24 academic year in a tapestry-making event hosted by London College of Fashion’s Lucy Orta.

Textile art has often been undervalued because of its association with women’s work within the heteronormative patriarchies that dominate Fine Art.

However, there has always been an exception to the rule, perhaps because of her fashion links or her partnerships Modernist artist Sonia Delaunay, 1885-1979, was able to find a showcase for textile art. She saw no distinction between her paintings and her so-called ‘decorative’ work, considering the latter an extension of her art rather than a lesser form. They were Born in Odesa, Ukraine, to a poor Jewish family, then adopted by a wealthy uncle, Henri Terk, taking his name. Sonia Terk studied drawing at the Karlsruhe Academy of Fine Arts in Germany before moving to Paris in 1906. Where she married art dealer Wilhelm Uhde, gaining French citizenship.

The bold colours of Fauvism heavily influenced her during her early years in Paris. Uhde introduced her to Robert Delaunay, who would become her second husband. Together, Sonia and Robert Delaunay pioneered Orphism, a fusion of Cubism and Neo-Impressionism. Sonia used this aesthetic in her paintings, textiles, and designs throughout her career.

In 1964, she became the first living female artist to have a retrospective at the Louvre Museum. Her works are currently housed in several prestigious museums worldwide.

Delaunay’s Modernist refusal to distinguish between fine art and applied art foreshadowed our Contemporary XD.

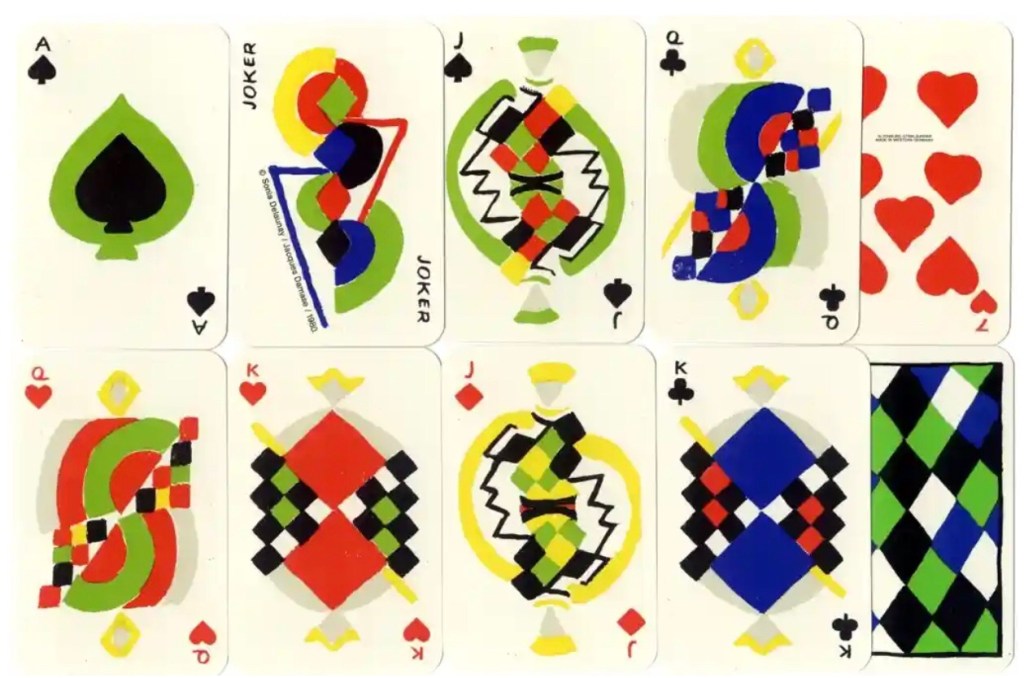

Being a cross-cultural polyglot, she was familiar with transitioning and altering modes of expression. Her aesthetic could manifest in various forms, whether it was a wall painting, a item of clothing, or a pack of cards. Her art was more than just visual; it was a lived statement.

So my clothes mountain is real; it is partly a Transition-based clear out, though I was surprised how little girly clothing I have. I had to reappraise my wardrobe after my tumour removal, as a 10-inch daily swelling and reduction of my waist has to be accommodated somehow. I’m going to try and find new homes for my unwanted clothes, and if I can’t, then I’m going to use them as art material. I’m about to own my problem and not discard it to the charity/landfill.

Leave a comment