I can’t find my sundress, I have a feeling it was already donated to charity long ago. For me it represented gender dysphoria and the worlds growing clothes mountain. What am I to make my dick and boobs out of?

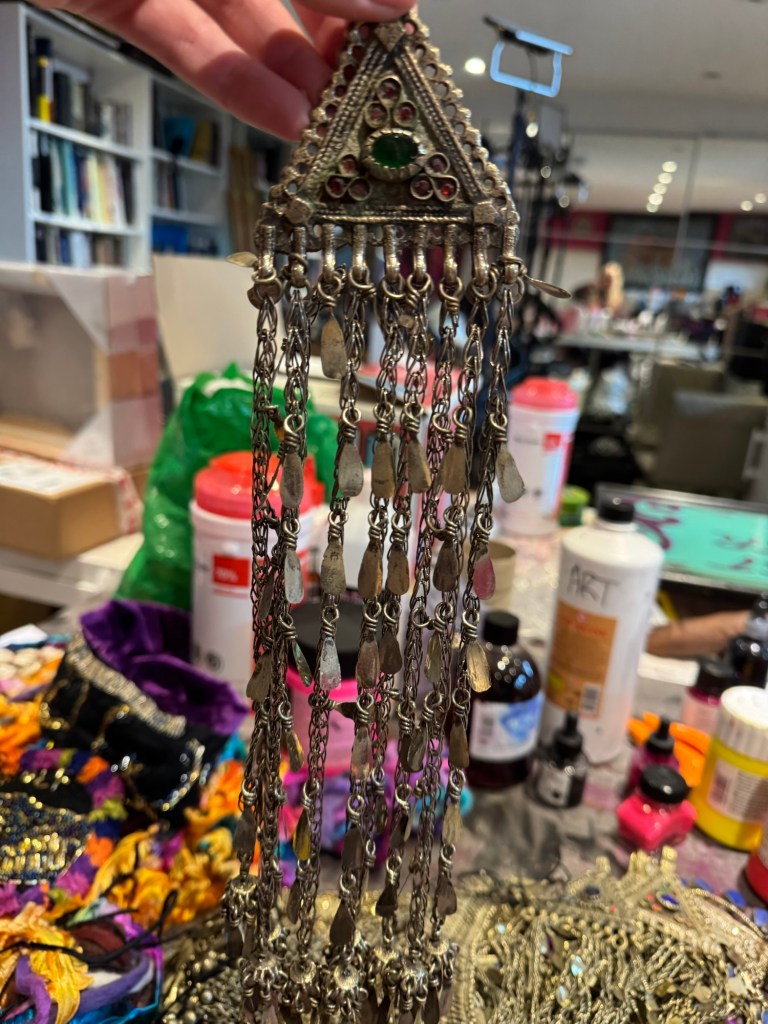

What I did find buried in my studio instead was some tribal belly dancing costumes and pile of tribal jewellery I’d collected from Afganistan.

I thought I’d given away all my ‘belly dancing’ costumes to a dance troup when I moved ten years ago… but no, here it was a little stash of stuff.

Then it hit me… here in a collection of little plastic bags was a story from the MAPA that perfectly represted Abstract Materiality and the meaning of 2050:2100

Once upon a time in Kabul, I imagine a group of Afghan women gathered for a wedding. One by one, the women slip off their headscarves and begin to dance, their jewellery chiming as they shimmy… could they do that today? It’s unlikely, but I hope so…

Afghan women’s dance costumes are legendary for their ornamentation, necklaces, massive silver earrings, layered headpieces with dangling coins or bells, and armfuls of bracelets. It was handmade and passed down through generations, and every piece tells a story of family, region, prayer, status, and even personal luck. It wasn’t just for the show. It was a woman’s savings account, a portable dowry, something to rely on if times got hard. Some pieces are hundreds of years old, with turquoise, carnelian, or lapis lazuli, some just bits of colourd glass and foil… all worked into the metal.

When the Taliban first took power in the late 1990s, everything changed overnight. Dance, music, and even colourful clothes were banned. Women gatherings were broken up, and anyone caught dancing faced harsh punishment—sometimes beatings, sometimes worse. Many women buried their costumes and jewellery in the ground, hid them in walls, or dismantled them to sell the pieces for food or safe passage out of the country.

Some jewellery was smuggled out by refugees, ending up in bazaars in Peshawar, Istanbul, Dubai, sold so families could survive. Whole traditions of embroidery and jewellery making slowed or disappeared, as the artisans who created them either fled, hid their work, or stopped altogether out of fear.

When the Taliban fell the first time in 2001, there was a flowering, weddings got louder, parties returned, and some families dug up their hidden treasures. Still, a lot had been lost, a lot had changed. With the Taliban’s return in 2021, is probably back to behind closed doors, if at all.

Despite everything, traces of Afghan women’s dance and jewellery live on.

I hope the Dance does too. Does the Afghan diaspora women teach the old dances to their daughters, wear family jewellery at weddings? Do folks preserve the jewellery traditions, collecting pieces and documenting the stories behind them.

If a woman puts on a jangling necklace or dances at a secret gathering, does this keep a link alive to the Afghan that existed before the bans and the violence. Is every step is a rebellion?

In Kabul is the talk not of dance these days, but education, freedom and simple survival?

In America a Tribal Style belly dance, or ATS, started in the 1980s with Carolena Nericcio and her troupe, Fat Chance in Portland Oregon. The style was a mashup of Middle Eastern and North African dance steps combined with Indian and Flamenco influences, performed in a group with heavy jewellery like those of Afgan women, big skirts, and an appropriated tribal aesthetic. By the early 2000s, ATS had exploded in popularity. It spread online, at festivals, and in studios across the U.S. and Europe, evolving into a whole movement, Tribal Fusion, Gothic Tribal, et al.

The appeal was clear: it was group-oriented, improvisational, and felt empowering to a lot of dancers who didn’t fit the mainstream, hyper-glamorous belly dance aesthetic. ATS wasn’t about performing for men or commercial gigs; it was about women dancing together, reclaiming space and owning their bodies.

So where does the CIA come in? The rumour, in the early 2000s, was that the U.S. government, including agencies like the CIA, supposedly funded or supported Middle Eastern and North African cultural programs in the States, including folk dance, music, and language, under the banner of cultural diplomacy. The goal was to increase understanding of Middle Eastern cultures and allegedly keep an eye on any radicalisation or unrest in diaspora communities after 9/11.

Some versions of the story claim that certain Tribal dance festivals or workshops got government grants, or that ATS instructors were quietly encouraged to promote a peaceful and empowering image of middle eastern culture. There are even whispers that the government monitored big festivals, not because they cared about dance, but because they were interested in who was showing up, what was being discussed, and how Arab and non-Arab communities were interacting.

So, is any of it true? Cultural grants and outreach programs did happen. I heard a lot of stories and rumours but there’s was is no clear evidence that the CIA specifically targeted ATS or belly dance as a front for anything nefarious. If the CIA was involved, it was probably as part of a much broader effort to understand and sometimes monitor cultural groups, not because they thought ATS dancers were up to anything.

Part of why this rumour refuses to die is that ATS is inherently political: it’s a dance form that borrows and blends cultures, often without deep knowledge of their origins which was blatantly problematic. I witness myself some proper nonsense in classes and dance festivals. However, in the 2000s, as the U.S. and U.K. was embroiled in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, there was an awkward tension in the dance world. American and British women were donning tribal costumes and dancing to Middle Eastern music, while people from those regions faced discrimination abroad and violence at home. Some dancers felt they were creating solidarity; however, many of us felt uneasy about appropriation. Against this backdrop, stories of CIA interest or interference didn’t sound so far-fetched.

But Belly dancing has always had an ‘interesting’ history. It all started with a tribe called the Ghawazee, sometimes spelled ghawazi. these were a group of dancers that worked around north africa and the eastern med. For centuries, they lived on the edges of polite society. The Ghawazee were a group of travelling women dancers and male musicians. It was a matriarchal tribe who settled in Egypt, especially around Luxor and Cairo, sometime in the 18th or 19th century. Foreign travellers were both scandalised and fascinated by the Ghawazee’s sensual style. It didn’t help that Ghawazee was used as a name that described a dancer/prostitute, which I pointed out to an ATS dancer who had Ghawazee tattooed ‘large’ on her hips and back. She thought it meant ‘slave to love’…well…. The Ghawazee broke a lot of social rules, they didn’t wear veils, they mingled freely with men, worked as courtesans. The Ghawazee weren’t just sex workers, they were community healers, confidantes, and often, spies.

They knew about birth control, herbal remedies, and the realities of childbirth. They taught brides how to pleasure their husbands and keep their own bodies healthy. In some villages, a Ghawazee woman might be the only person you’d trust with questions about intimacy, reproduction, or healing after childbirth. This wasn’t just about sex, it was about survival. The Ghawazee’s knowledge kept women healthy and they were paid for their expertise. In a way, they were the original sex educators and gynaecologists, long before those were even professions.

Because the Ghawazee had access to all parts of society, men’s gatherings, women’s spaces, royal harums, and street festivals, they worked as informants or spies. French and British colonial authorities, as well as local rulers, would hire Ghawazee to gather information. Their dancing was a perfect cover. You can see them in many orientalist paintings of the 19th century, they are the ladies wearing stripy pantaloons and waistcoats, keeping an eye on the visiting foreign painters no doubt!

By the late 19th century, the Egyptian government started cracking down on the Ghawazee, pushing them out of Cairo and labelling them as a corrupting influences. Still, their influence stuck around. Many of the moves and styles we now call belly dance come straight from the Ghawazee tradition.

At the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, ‘Little Egypt’, Fahreda Spyropoulos who was actually Ghawazee from Syria, performed her version of what she called ‘The Dance’. The New York Times christened it ‘Belly Dancing’ because you could see her belly move. Even ATS dancers completely misunderstood how the dance wasn’t about your belly but about your pelvic floor!

It’s easy to think of climate change in terms of melting ice or rising seas. But the first things to vanish in times of massive upheaval are almost always the things that don’t make headlines, songs, dances, jewellery, rituals. This is the reality for MAPA, Most Affected People and Areas, the communities on the front lines of climate chaos, cultural erasure, and forced change.

Small island nations like Tuvalu and Kiribati watch the ocean eat their beaches, and with every high tide, a little more of their language and tradition slips away. In the Amazon, Indigenous families flee wildfires, leaving behind sacred forests and the knowledge. In Afghanistan, the return of the Taliban means that the costumes and dances that once defined a women are hidden in walls, buried in gardens, or, heartbreakingly, sold for a ticket out.

MAPA, Most Affected People and Areas, aren’t just facing floods and droughts. They’re fighting to keep their cultures alive in the face of erasure. Soon everything will change for us all.

Leave a comment